I’m serving a lot of text files with my web server and I want them to be displayed correctly.

The Problem: Garbled Unicode Text

The default encoding for the text/plain Content-Type is us-ascii as specified in RFC1341.

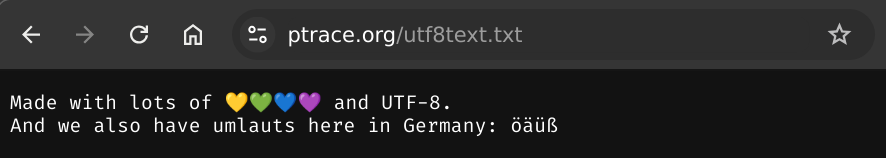

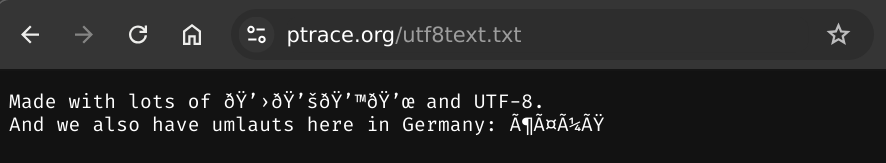

This default is wrong when a text file contains characters that are not part of the default charset, like umlauts, emojis.

The result is garbled text:

Understanding the Content-Type Header

If you’re not interested in technical details, jump to the solution.

Header fields can be explored with curl.

$ curl -I https://ptrace.org/plaintext.txt

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 2941

Content-Type: text/plain

Date: Sat, 21 Dec 2024 07:48:13 GMT

Last-Modified: Tue, 15 Oct 2024 05:30:40 GMT

Server: OpenBSD httpd

The Content-Type can be seen as the web-version of the file extension. Header fields are delivered before the actual file, and contain various instructions for the browser that are useful to know before starting to load the data.

The browser knows which content types it can handle. If an unknown content type is encountered, the data is offered for download.

Some examples:

- text/html → needs to be processed (rendered) and the result is displayed

- text/plain → can be displayed without processing

- text/xml → can be reformatted nicely and then displayed

- application/pdf → can be displayed using the pdf viewer plugin

- video/mp4 → can be displayed using the video player plugin

- image/jpeg → can be displayed using the jpeg library

For binary content types like video and images, this is sufficient, because there’s no encoding in place.

Why a text-type is not sufficient

For text based content types, like text, xml, html and so on, this is not sufficient. Technically, text is binary data as well, but there are different ways to store text, and we need to know which one was used, in order to decode it.

In the early computer days, when memory was sparse, only the most necessary characters were supported.

Those were the 127 characters defined in us-ascii.

As mentioned in the beginning, this is the default character set for content type text/plain.

There’s no “ö”, no “ä”, no “ü”, no “ß” in us-ascii, and therefore these characters cannot be displayed.

However, one ascii character is stored in one byte. And one byte has 8 bits, which can store 256 values (2^8).

This means us-ascii only occupies half of the available space. When computers got more popular, users demanded to be able to use their local character sets.

The half byte that could be used in addition is not enough for all of the worlds characters and symbols.

The solution was to make the second half of the byte switchable. And this switch is called Code Page. The code page idea was not new. It was taken from another encoding, which happened to exist in parallel to ascii. It was called EBCDIC, and was developed and used by IBM. EBCDIC had code tables.

The code table concept was then adapted in ASCII (or 8 Bit ASCII) and called code page. Ascii with an applied code page was called Extended ASCII.

Note: The terminology ascii (or ASCII) can be used for both: us-ascii, which is 7-bit ascii and only contains the characters used in the United States. And extended ascii, which is the 8-bit ascii variant that contains us-ascii plus 128 more characters from one of the code pages.

Here is the byte value of character “ö” in different encodings:

- Extended ASCII (Code Page 819) →

0xf6 - Extended ASCII (Code Page 1252) →

0xfc - Extended ASCII (Code Page 437) →

0x94 - EBCDIC (CCSID 7) →

0xd0

Now it’s clear that the information “this data is of type text” is not sufficient to read it:

If we see a byte with value 0x94, we don’t know what character it is without additional information.

In ASCII with Code Page 437, it is “ö”.

In ASCII with Code Page 819, this code point is unused.

In EBCDIC Code Page 7, it would be the character “m”.

These combinations adds up to hundreds of ways how data can be interpreted as text. And it explains why selecting the wrong encoding often only leads to half of the characters being garbled.

Luckily, most of this mess is history now, thanks to the development of unicode, which defines an encoding that can take up to 4 bytes and is big enough for all the language characters in existence… and emojis.

Unicode itself is is a concept of how code points are organized. The technical encoding exists in more than one flavor, however, the most common character encoding is UTF-8.

UTF-8 is a variable width encoding, which means it can store common characters in one byte, but can use up to 4 bytes per character to address rarely used characters. In addition to that, it’s compatible with us-ascii, which means the first 127 characters are byte compatible between ascii and utf-8.

This means utf-8 can be use instead of ascii without breaking compatibility. A valid 7-bit ascii file, it also a valid utf-8 file.

Due to this and the variable length, utf-8 can not store 2^32 characters, but only 2^21. Which is 2097152 (way more than 256, and enough to address all of the characters in the world).

This could have been a happy ending, if we wouldn’t have started to squeeze emojis into unicode. The old, yellow standard emojis were fine, but then people wanted emoji variants and combinations.

- This is 7 characters displayed as one → 👨👩👧👦

Source:

👨‍👩‍👧‍👦

- This is 10 characters displayed as one → 👨🏿👩🏻👧👦🏾 (really, try to copy one of them)

Source:

👨🏿‍👩🏻‍👧‍👦🏾

Can we please going back to using images for stuff like this?

The solution: Content-Type charset subtype

In the previous chapter, I described that knowing that some data is text, is not sufficient to interpret the data.

For this reason, the Content-Type header supports an additional subtype. This subtype can contain charset information, which can give more details about the encoding of the text. Like Content-Type: text/html charset=latin1 would announce a ISO-8859-1 document by it’s nickname “latin1”.

In practical terms, it’s rare nowadays to encounter text that’s not utf-8 compatible, and therefore the solution is to add the utf-8 charset information to the text/plain type of the Content-Type header.

$ curl -I https://ptrace.org/utf8text.txt

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 98

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

Date: Sat, 21 Dec 2024 08:15:02 GMT

Last-Modified: Sat, 21 Dec 2024 07:53:26 GMT

Server: OpenBSD httpd

Fixing the OpenHTTPd configuration

Let’s start by making OpenHTTPd aware of more mime types.

The documentation shows how to add a list of mime types to /etc/httpd.conf:

types {

include "/usr/share/misc/mime.types"

}

This makes OpenHTTPd aware of all the default content types described in this file.

The file /usr/share/misc/mime.types contains the following line, which creates a link between the file extension .txt and the type, that is delivered using the Content-Type Header.

text/plain txt

This line needs to change.

Instead of including the file, the content can also be added to /etc/httpd.conf directly.

Do not change /usr/share/misc/mime.types directly, it will be overwritten with the next OpenBSD Upgrade. You can create a modified copy and include the copy instead.

The charset can be added to the text/plain entry by changing it to text/"plain; charset=utf-8".

The quotes are needed, otherwise charset=utf-8 would be interpreted as file extension, which would be invalid and httpd wouldn’t start.

types {

application/atom+xml atom

application/font-woff woff

application/java-archive jar war ear

...

text/"plain; charset=utf-8" txt

...

video/x-ms-asf asx asf

video/x-ms-wmv wmv

video/x-msvideo avi

}

It’s not necessary to add all the mime-types, but it’s a good idea to do so.

With this configuration, the the proper Content-Type header with charset subtype will be delivered and textfiles containing unicode characters will be displayed correctly.